The Mumboism movement was a significant anti-colonial, millennialist religious movement that emerged in the early 20th century among the Luo and Kisii (Abagusii) communities in Kenya’s Nyanza region, particularly around South Nyanza (modern-day Homa Bay, Migori, and Kisii counties). It arose as a response to the oppressive conditions imposed by British colonial rule, blending traditional beliefs with a radical vision of liberation. Below is an exploration of its origins, beliefs, spread, impact, and eventual suppression.

Origins and Context

Mumboism began around 1913, though some sources suggest its roots may trace back to earlier resistance movements. The movement was founded by Onyango Dunde, a man from the Alego region of the Luo community, who claimed to have received a divine revelation. According to oral traditions, Dunde was swallowed by a serpent in Lake Victoria (referred to as “Mumbo,” a term meaning “spirit” or “deity” in Dholuo), which spoke to him and granted him a prophetic vision. This serpent, often interpreted as a manifestation of a traditional deity, instructed Dunde to lead his people against colonial oppression and the encroaching influence of Western Christianity.

The socio-political context of the time fueled Mumboism’s rise. The British colonial administration, established in Kenya by the late 19th century, imposed harsh policies on African communities. In Nyanza, the Luo and Kisii faced heavy taxation, forced labour (such as the kipande system requiring Africans to carry identification for labour control), land alienation for European settlers, and the disruption of traditional governance structures. Christian missionaries, often working hand-in-hand with colonial authorities, sought to replace indigenous beliefs with Christianity, further alienating communities. The Kisii, primarily agriculturalists, and the Luo, who combined fishing, farming, and pastoralism, both felt the weight of these changes, leading to widespread discontent.

Beliefs and Practices

Mumboism was a millennialist movement, meaning it promised a radical transformation of the world order. Its core belief was that the serpent deity, Mumbo, would bring about an apocalyptic event to expel the British and their African collaborators, restoring prosperity and autonomy to the people. Key tenets included:

- Rejection of Colonial Authority and Christianity: Followers were urged to abandon European ways, including Christianity, colonial taxes, and labour demands. Mumboism preached that the British would be driven out, often predicting their departure by supernatural means, such as being swallowed by Lake Victoria.

- Return to Traditional Practices: The movement encouraged a revival of indigenous rituals and beliefs, rejecting mission education and churches. For instance, followers were told to stop wearing European clothes and to return to traditional attire.

- Communal Feasting and Sacrifice: Mumboism involved communal gatherings where followers would feast, often sacrificing cattle to appease the Mumbo spirit and ensure prosperity. These feasts also served to strengthen community bonds and resistance.

- Promise of Utopia: Adherents believed that by following Mumbo’s teachings, they would gain wealth, abundant harvests, and freedom from colonial oppression. The movement tapped into a deep longing for a return to a pre-colonial golden age.

Mumboism blended traditional Luo and Kisii spiritual beliefs with anti-colonial sentiment. The serpent deity was a powerful symbol in both cultures, often associated with water spirits and divine authority, resonating deeply with local cosmologies.

Spread and Influence

Mumboism initially spread among the Luo in Alego and Gem but quickly gained traction among the Kisii, particularly in South Nyanza, where the two communities lived nearby. By the late 1910s, it had attracted thousands of followers, cutting across ethnic lines—a rare feat in a region where ethnic tensions were often exacerbated by colonial policies. The movement’s appeal lay in its promise of liberation at a time when colonial rule was intensifying, especially during World War I (1914–1918), when the British conscripted Africans as porters and soldiers, further straining communities.

The movement was largely non-violent, focusing on spiritual resistance rather than armed rebellion. However, its rejection of colonial authority, such as refusing to pay taxes or work on colonial projects, made it a significant threat in the eyes of the British. Mumboism also challenged the influence of African “loyalists,” such as chiefs appointed by the colonial government, who were often seen as collaborators. For example, Chief Odera Ulalo, a prominent Luo chief, had provided porters for colonial expeditions, earning favour with the British but resentment from his people, some of whom turned to Mumboism as a form of protest.

Colonial Response and Suppression

The British colonial administration viewed Mumboism with alarm, seeing it as a potential catalyst for widespread rebellion. The movement’s anti-Christian stance also angered missionaries, who pressured the colonial government to act. By 1919, the colonial authorities declared Mumboism a “subversive” movement and began cracking down on its followers.

- Arrests and Deportations: Onyango Dunde was arrested in 1919 and deported to Lamu, a remote coastal island, where he reportedly died in the 1920s. Other leaders were also rounded up and exiled, often to distant parts of Kenya like Marsabit, to break the movement’s momentum.

- Use of Force: Colonial police, often accompanied by local militias (such as the ogulmama among the Luo), raided villages suspected of harbouring Mumboists. These raids sometimes turned violent, with followers resisting arrest. In some cases, cattle—the lifeblood of many Luo and Kisii families—were confiscated as punishment.

- Divide-and-Rule Tactics: The British exploited ethnic divisions to weaken Mumboism, encouraging “loyal” factions within the Luo and Kisii to oppose the movement. This exacerbated tensions between communities, though Mumboism itself had initially united them against a common enemy.

Despite these efforts, Mumboism persisted into the 1930s, with underground gatherings and sporadic revivals. The movement’s ideas influenced later anti-colonial movements in Nyanza, such as the Dini ya Msambwa among the Luhya, which also blended traditional beliefs with resistance to colonial rule.

Impact and Legacy

Mumboism had a lasting impact on the Luo and Kisii communities and Kenya’s broader anti-colonial struggle:

- Cultural Revival: The movement reinforced the importance of traditional beliefs and practices, providing a counter-narrative to the Christian missionary agenda. It reminded communities of their pre-colonial identity and autonomy.

- Anti-Colonial Resistance: While Mumboism was not a political organisation in the modern sense, its rejection of colonial authority inspired later, more organised forms of resistance. It laid the groundwork for future movements, including the Mau Mau uprising in the 1950s, by showing that spiritual and cultural resistance could challenge colonial power.

- Ethnic Unity and Division: Mumboism briefly united the Luo and Kisii against colonial rule, demonstrating the potential for cross-ethnic solidarity. However, the colonial crackdown and divide-and-rule tactics also deepened mistrust between the two groups, as some were coerced into collaborating with the British against their neighbours.

- Historical Memory: Today, Mumboism is remembered in Nyanza as an early example of resistance to colonial oppression. Scholars like Bethwell Ogot and Nancy Schwartz have documented its significance, drawing on oral histories to highlight its role in shaping anti-colonial consciousness.

Modern Relevance

The Mumboism movement offers lessons for understanding resistance to oppression. It shows how spiritual beliefs can become a powerful tool for mobilising communities against injustice, a phenomenon seen in other parts of Africa, like the Maji Maji Rebellion in Tanganyika (1905–1907). It also highlights the resilience of African traditions in the face of colonial attempts to erase them. However, the movement’s suppression underscores the challenges of resisting a well-armed colonial state, especially when internal divisions are exploited.

In contemporary Kenya, the legacy of Mumboism can be seen in the continued reverence for traditional spiritual practices among the Luo and Kisii, as well as in the region’s strong tradition of political activism. The movement’s emphasis on communal solidarity and resistance to external domination resonates with modern struggles for cultural preservation and self-determination.

Mumboism, though short-lived, was a powerful expression of African agency in the face of colonial domination, blending the spiritual and political to envision a future free from oppression. Its story is a testament to the enduring human desire for freedom, even in the darkest of times.

Conflict between the Luo and Kisii

During the colonial period in Kenya, tensions between ethnic groups like the Luo and the Kisii (also known as the Abagusii) were often exacerbated by British colonial policies, which pitted communities against each other to maintain control. However, there are no widely documented historical accounts specifically detailing large-scale incidents of the Luo killing the Kisii during this time. Instead, the interactions between these groups were complex, involving both conflict and cooperation, shaped by pre-existing rivalries, colonial manipulation, and economic pressures.

One notable dynamic during the colonial era was the Mumboism movement, which emerged around 1913 among the Luo and Kisii in the Nyanza region. This millennialist cult, led by Onyango Dunde, preached resistance against colonial rule and its associated Christian missions, predicting the expulsion of the British and their supporters. The movement gained traction among both the Luo and Kisii, who were frustrated by colonial taxes, forced labour (like the Kipande system), and land alienation. However, the colonial authorities viewed Mumboism as a threat and suppressed it harshly, deporting and imprisoning its followers in the 1920s and 1930s. While this movement united some Luo and Kisii against a common enemy—the British—it also created tensions. The British often pitted ethnic groups against each other, arming “loyal” factions to suppress “rebellious” ones, which could have led to localised violence. For example, colonial records suggest that the British sometimes used Luo porters or recruits, like the 1,500 provided by Chief Odera in 1900 for an expedition against the Nandi, to enforce control in neighbouring areas, including Kisii territory. This could have sparked retaliatory clashes, though specific instances of Luo killing Kisii in this context are not well-documented.

Another layer of tension came from economic and territorial competition. The Luo, a Nilotic group, and the Kisii, a Bantu group, lived nearby around Lake Victoria, particularly in areas like South Nyanza (now parts of Migori, Homa Bay, and Kisii counties). The Luo had migrated into the region between the 15th and 18th centuries, often interacting with Bantu groups like the Kisii through trade, intermarriage, and conflict. During colonial times, the British exacerbated these dynamics by designating districts along ethnic lines, such as Kisii District for the Kisii, which fostered a sense of territorial ownership and exclusion. This led to disputes over land and resources, especially as colonial policies displaced communities and forced them into closer proximity. For instance, grazing land conflicts and cattle rustling, which predate colonial times, became more volatile under colonial pressures. The Kisii, known for their agricultural practices, and the Luo, who combined fishing, farming, and pastoralism, occasionally clashed over fertile land or cattle, with violence sometimes erupting. However, these conflicts were typically small-scale and not indicative of widespread ethnic killing.

A specific story of violence might be imagined from the broader context of the Mumboism suppression. In the early 1920s, as the colonial government cracked down on the movement, it often relied on local militias or colonial “police” (known as ogulmama among the Luo) to enforce order. If a Luo ogulmama unit was deployed to a Kisii area to arrest Mumboism adherents, tensions could have escalated into violence. Imagine a scenario where a colonial officer, backed by a Luo-led unit, raided a Kisii village suspected of harbouring Mumbo cultists. The Kisii villagers, resisting arrest, might have fought back, leading to a skirmish where several Kisii were killed by the Luo unit under colonial orders. Such an event would not reflect a deep-seated ethnic vendetta but rather the tragic outcome of colonial divide-and-rule tactics, where African communities were forced into conflict to serve British interests.

While the Kisii and Luo generally maintained peaceful relations—engaging in barter trade and even working together to resist cattle raiders—the colonial era’s artificial boundaries and economic pressures did create opportunities for violence. However, narratives of large-scale ethnic killings between the Luo and Kisii during this period are not supported by historical records. Instead, the real violence often came from the colonial state itself, which suppressed both groups through brutal policies and military actions, as seen in the broader context of Kenya’s colonial history, like the Mau Mau uprising, where similar divide-and-rule tactics were used.

If you’re looking for a more detailed or specific account, it might require digging into local oral histories or colonial archives, which often underreport African perspectives. The story of colonial-era Kenya is more about how the British manipulated ethnic tensions than about inherent enmity between groups like the Luo and Kisii.

Related Posts

- How to Start a Mahindi Choma Business in Nairobi: Ksh 5,000 Daily Profit

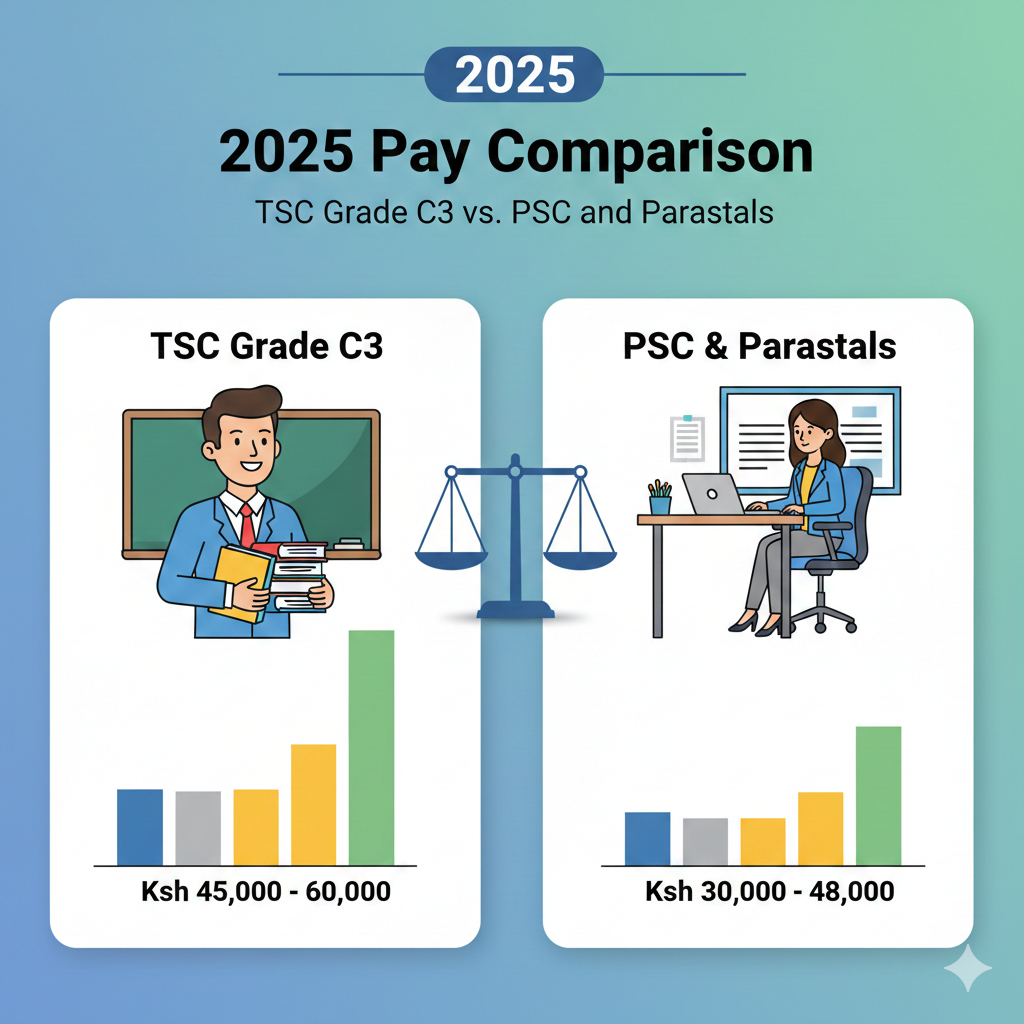

- Kenya’s 2026 Pay Comparison: TSC Grade C3 vs. PSC and Parastatals

- Where to Invest in Kenya 2026: Top 5 High-Return Sectors & Business Opportunities

- How to Start a Butchery Business in Kenya: Costs, Licences, and Tips (2026)

- U.S. Airstrikes in Nigeria: Geopolitical Manoeuvre or Resource Grab?

- How to Start a Profitable Salon in Kenya (2026): Costs, Licences, and Requirements

- The Difference Between Hospitality and Entertainment Establishments Under Kenyan Law

- Is Ruto’s Handout Economy Hijacking Kenya’s Future? Why Patronage Over Progress Spells National Disaster.

- SHA: Emergency Evacuation and International Referrals – Access to Critical Care

- SHA: Dental and Optical Benefits – Caring for Your Smile and Vision

- SHA: Maternity Coverage – Comprehensive Care for Growing Families

- SHA: Outpatient Benefits Decoded – Your Day-to-Day Medical Coverage

- SHA: Inside Your Inpatient Coverage – Hospital Care Benefits Explained

- SHA: Your Benefits Breakdown – What Every Teacher Gets Based on Job Group

- TSC Unveils Comprehensive Medical Cover for All Teachers Starting December 2025

- Tragedy Strikes KJSEA Marking Exercise as Examiner Dies at Machakos Girls High School

- Shadows of Empire: How the West Maintains Control in Africa

- Why Senator Okiya Omtatah Wants to Abolish the Bomas National Tallying Centre (And Why It Matters for 2027)

- What to Study Now for a Successful Career in Kenya’s Future (2026-2050)

- AUDIT SHOCK: Only 3,000 Schools Get Capitation Funds as Govt Cracks Down on “Ghost Students”

- TSC’s Promotion Blueprint: How Teachers Earn Their Next Grade